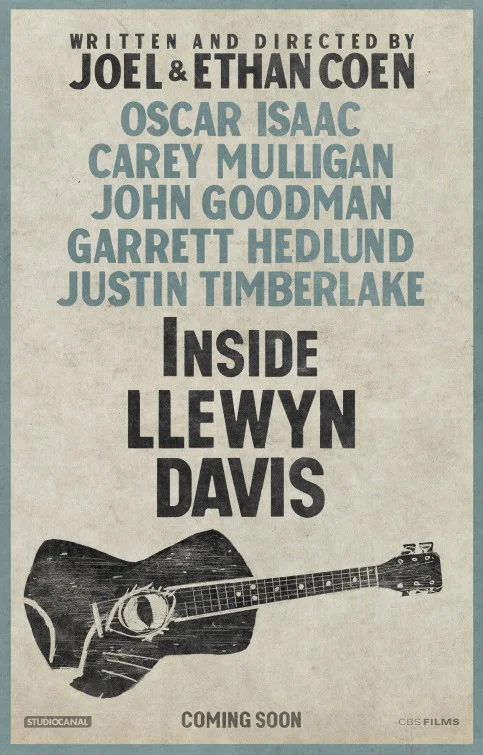

Fare Thee Well: Inside Llewyn Davis

Inside Llewyn Davis, a film by the Coen brothers and released in 2013, is a portrait of a specific man in a specific time, playing music that is timeless.

The story follows a struggling musician in the Village, NY, 1961, just before Dylan blew the scene wide open. This portrait of folk music highlights the mix of acoustic strings, blues, simple harmonies, lyrics that spin stories and melodies that carry the weight of their history. The music is presented as full songs, allowing the audience to fully appreciate the performers, both aurally and visually. The camera carefully finds the best way to show the song, whether exploring the various views of the stage in the Gaslight Club, or simply settling on the arist’s face during a solo audition.

The main performer of the piece is the title character, Llewyn Davis. Although musically very talented, he just can’t get life right. He is constantly getting in his own way; he wants success and needs a few dollars, but is constantly pushing away the people who are kind enough to lend him a couch. He loses important items (for example, a cat) and lets his emotions run wild with immature outbursts. Amazingly, his friends seem to forgive him fairly easily throughout the film.

But through it all, he has the music. He is clearly talented, but not commercial. He is comfortable playing in front of a crowd, but is reluctant to perform for friends, an act he considers his way to make a living. When he does choose to play, for his aged father or to pass the time in a car trip - he is really playing for himself. His songs are all internal; the audience gets to see a bit of Llewyn Davis, but never fully inside.

This is best demonstrated by how the Coen brothers, such precise filmmakers, shoot the music scenes. They let the songs breath, play with light and shadows, and allow the camera to find new perspectives on their subject. One particular shot is not only artfully constructed, but is illustrative of Llewyn Davis. In the opening of the film, which shows Davis strumming and singing alone on a stage, guitar in hand and perched on a stool. The stage light shines brightly down upon him, acting as a spotlight and a barrier between him and the audience; they are permitted to watch his presentation, but through a divider.

Oscar Issac is the key to this film. He delivers full force a character that is very flawed, very artistic, very human. He plays the guitar and sings live, often with long takes and never falters to elevate the music and acting to a high level. During a scene on the drive to Chicago, he sings a lighthearted song in his upper register, even inviting the “crowd” to join in, and does some fine guitar work; his face, however, ranges between the mask of performing and the melancholy he really feels. It takes skill to pull music and acting together so brilliantly, yet Issac does it seemingly effortlessly.

The supporting cast is comprised of various guests that range from serviceable performances to excellent turns (especially the cat). Carey Mulligan attacks her lines and the character comes in punching, but her staccato performance is too much of a one note flatline. If her performances had a bit more range (rather than always angry and jabbing words like ASSHOLE), we could see more of her connection to Llewyn. Near the end of the film, she does some more interesting and quiet work, but too little too late. John Goodman was fine as a typical Coen character and there are shades of his Lewbowski character - blustering and making threats that he couldn’t possibly carry out. Timberlake plays nice guy Jim, does well musically, and injects some fun into the pop recording scene.

Jeanine Serralles puts in a solid performance as Llewyn’s sister - familial, nagging, loving, frustrated, yet forgiving; they were quite believable as siblings. Also, Serralles manages to pitch her voice for the times, evoking the 60s housewife. The most stellar performance of the supporting players is F. Murray Abraham, who portrays a music producer that Llewyn auditions for; he is stoic, but gives the guy a chance and is then honest with him about his chances of making it big. He correctly asses Llewyn and his talent (he suggests getting back together with your partner), which becomes even more heartbreaking as his partner has committed suicide. Llewyn must begin to make new choices after his encounter with Abraham.

The film relies on a light plot, but focuses more on a wandering through a week in this musician’s life. The washed out colors and neutral pallet compliments Llewyn’s characterization and the 60s setting is appropriately represented by the production design. In the end, the music is the undercurrent of the film and stays with audiences long after the credits fade.